Less crypto, more economics, history, and philosophy this week.

Thing #1: History Rhymes

I came across this passage this week in a book I’m reading, and it immediately stood out to me:

… [there was] an emerging belief among many laborers that the nation had entered a dangerous and potentially fatal period in its history. They rejected the conclusion of middle- and upper-class Americans that the nation's ills stemmed from the misguided embrace of radical, un-American ideologies like socialism. Instead, workers offered a different diagnosis and prescription, one shaped by a rising working-class that identified a crisis caused by a headlong and unrestrained industrialization that enriched and empowered a small elite while impoverishing the masses. They went further by stressing inclusiveness across traditional worker divides of skill, ethnicity, race, and gender, in addition to the democratization of industry. They also asserted that citizenship must guarantee not only political rights but economic rights as well, and called upon the state to guarantee them. This language of protest offered a vision of an alternative, cooperative society… At its core lay the conviction that a principle—that economic opportunity and upward mobility were open to all honest, hardworking men and women of solid character and good habits—had been nullified by laissez-faire automation and capitalist-friendly government policy. Finding themselves no longer able to rise, American workers were trapped as members of an underclass of poorly paid wage earners, without the freedom and independence of true citizens… They also focused on a particularly distressing aspect of labor's plight—its seemingly permanent condition, a fact that called into question America's free labor tradition that had previously always characterized wage work as a temporary stage in an upward journey to eventual independence. They spoke of thwarted opportunity and "the crystallization of society more and more into distinct classes, and a man born in one of them can never hope to reach the other." This "crystallization,” they argued, stemmed from the growing power of monopolies and corporations to crush competitors, potential entrepreneurs, and labor organizations… Some of its proponents called for the abolition of the wage system and the adoption of cooperative production. They also embraced solutions that called for a greater role of the state in protecting independence, opportunity, and equality… Moreover, they voiced another, starker, aspect of working-class life: a foreboding sense of impending doom. Reflecting the popularity of apocalyptic rhetoric that suggested the very fate of the republic hung in the balance, they laced their testimony with bleak references to imminent social revolution.

This book talks about large and growing inequality driven by “unrestrained industrialism,” automation, and large monopolies, the emergence of a “newly empowered elite,” corrupt politics and special interests, rising interest in socialism and “cooperative production,” the idea that citizenship should guarantee some degree of economic rights, that the underclass feels trapped, and the threat of “social revolution.”

If I asked you to guess what time period it’s describing, what would you say? Would you be surprised to learn that it’s describing an era around 150 years ago? It sounds like it could be describing the world of today, doesn’t it?

These passages come from a book describing the Gilded Age at the end of the 19th century (note that I took some liberties with the wording of the quote to make it sound a bit more modern, e.g., substituting “automation” for “mechanization”). During this time, rapid industrialization and economic growth led for the first time to the sudden emergence of a new, wealthy, powerful, elite group of businessmen known as “robber barons.” It was a period of rapid growth but also of enormous inequality and labor discontent. It saw tense political division and hostility towards immigrants. The parallels to the present time are truly chilling.

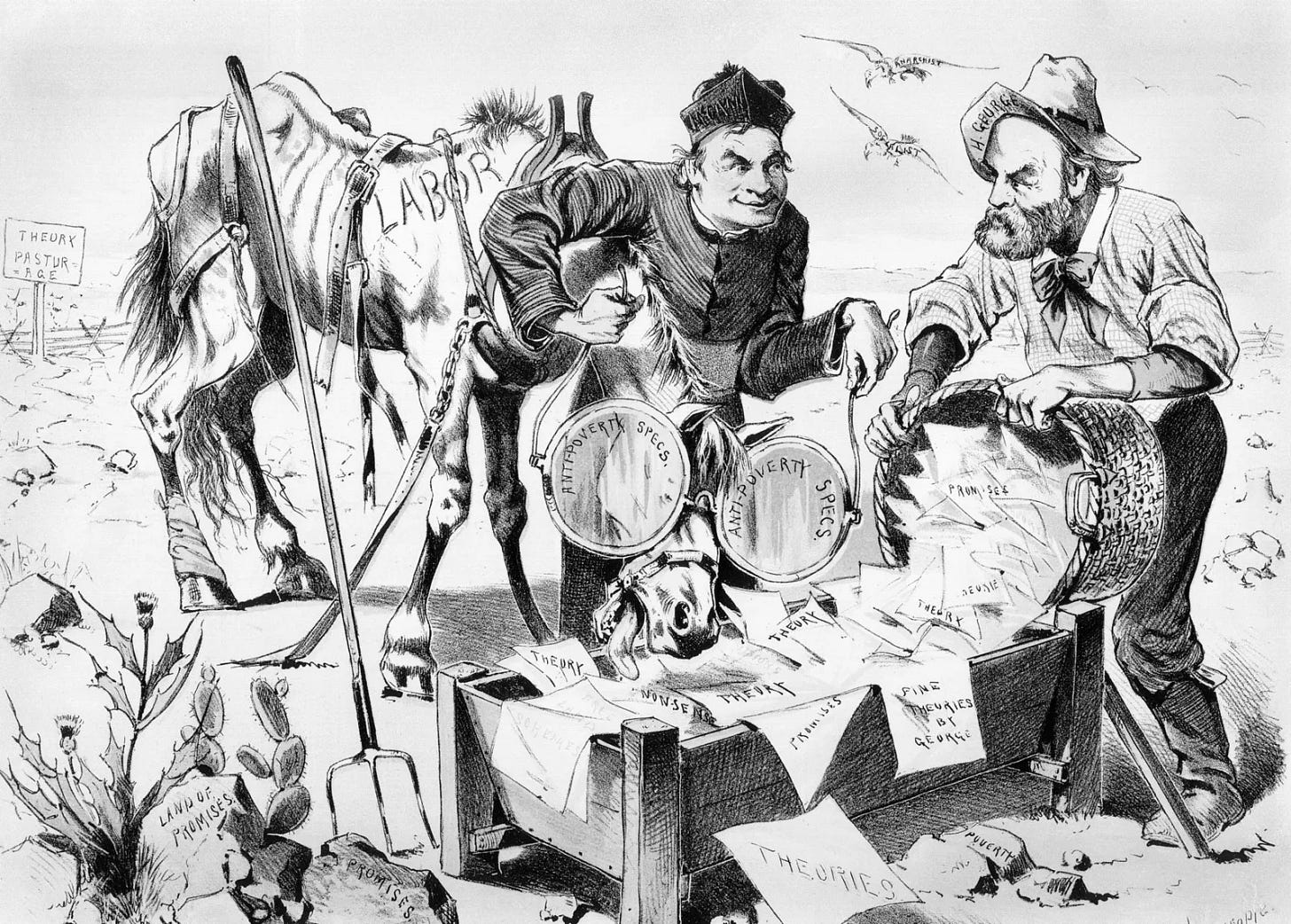

Henry George’s masterpiece, Progress and Poverty, emerged from the Gilded Age. It describes a world in which, in spite of massive economic growth, the working class are unable to escape from poverty. It attempts to solve the paradox of why economic progress and poverty go hand in hand and why the one doesn’t seem to solve the other. In George’s opinion, the core issue—what the passage above calls the “permanent condition” of “labor’s plight”—is land and the rents that elites are able to extract from monopolizing it. By George, the only way to fix the problem is radical land reform. That reform never happened.

Things today are better in some important ways: the life of the poor in America isn’t nearly as wretched as it was then, due to welfare, better public health, public schooling, etc.. But the wealth gap still exists and poverty is still a serious issue. Nearly 40 million people in this country, including 12 million children, live below the poverty line—and this is to say nothing of the situation globally. It’s a problem for everyone, not just the poor: many poor kids will never reach their full potential and may never make a positive contribution to society or pay taxes, as their education may be interrupted or cut short. They may not even have enough food to eat.

Poverty is stubbornly persistent. In hundreds of years of trying to understand it, explain it, and fight it, opinions still differ about what really causes it and how to fix it. I was attracted to the crypto space as a way to build a better, fairer, more inclusive economic system. I’m still hopeful that we’ll get there, but a lot of the current trends worry me, e.g., the scarcity of digital land. If we want to do better, it’s absolutely essential that we study history and learn its lessons. That’s a good place to start.

For more: Read Are We Living in the Gilded Age 2.0?, The Gilded Age, Progress and Poverty, or for a more modern take, Henry George and the Crisis of Inequality

Thing #2: Aging, Sickness, and Death

When things are going well—when you’re young, healthy, and comfortable—it’s easy to forget what’s coming. Many of us, myself included, lead relatively sheltered lives. We’re not often directly exposed to suffering: we don’t experience too much suffering ourselves, in our daily lives, and we may not often witness the suffering of others.

But this doesn’t change the fact that the reality of life is suffering. Suffering and comfort are like war and peace: in the same way that peace is not a state in and of itself, it’s merely a short-lived, temporary interlude between wars, comfort is a temporary interlude between episodes of suffering.

While many forms of suffering are avoidable or preventable if we live cautiously and prudently and take care of those around us, no one can avoid suffering due to sickness, old age, and death.

I find it extremely helpful to remind myself of this from time to time—especially while I am in the prime of my life, and when I feel insulated from suffering. The best reason, I think, is the one that Steve Jobs articulated in his famous, fatalistic commencement address: everything else shrinks in comparison to death. It just puts everything else in perspective and focuses the mind on what really matters. Look at yourself in the mirror once a day and ask yourself, “If today were the last day of my life, would I want to do what I am about to do today?”

There are two ways I do this. One is through a form of meditation called maraṇasati, or “mindfulness of death.” This sort of meditation has a long history in both the Eastern and Western tradition, and I highly recommend it for helping keep your perspective.

The other is through my father, who turns 99 soon. While he was remarkably healthy and active until quite recently, he’s experienced quite a bit of cognitive and physical decline recently, which is inevitable given his age.

As he keeps getting older, his life keeps shrinking. He used to publish, travel, and speak at conferences regularly. He had an active social life. Those things are all finished now, and nearly everyone he was close to has passed away (what happens when you live so long). First he stopped writing and publishing. Then he officially retired from teaching, but continued to teach one course. Finally, he stopped doing this too, just a few years ago.

He used to walk an hour each way, to and from the university. Then he cut back to a 30 minute walk to his favorite cafe. Then he reduced it to a short walk in the park. Now, he only goes out with help, in a wheelchair, and only when the weather is sunny and warm. His life has narrowed, then narrowed further. His recent onset of dementia is like a gauzy curtain being thrown over what little is left.

He’s withdrawn into the comfort of the home he’s lived in for decades. Recently, he spent some time in a long-term care facility, which meant that even his home was taken away from him. He was put in a spartan room with a bed, a dresser, a small table, and a TV. Nothing else.

He’s experiencing death in extremely slow motion: everything he knows, all the people he’s ever loved, everything he owns and is familiar and comfortable with, all of his habits and routines, even his very sense of self, are slowly being taken away from him. This might be something to lament, or to fight against—rage, rage against the dying of the light!—except that it happens to literally all of us and we are entirely helpless to prevent it. And there’s little lamentable about making it to 99 and still being in decent health!

Witnessing this process, it amazes me that, ultimately, we need very little to be healthy, happy, comfortable, and successful. And the more we’re able to be comfortable and happy with whatever we have, no matter how little or how simple, the happier and more content we’ll be, regardless of the circumstances—and the easier it will be to let go of things when the time comes. As I enter a phase of my life where things are growing, not shrinking—where I’m accumulating things, and people, and experiences, and artifacts—it’s extraordinarily helpful to be reminded of this, of where all of us are headed. It helps me focus on the things that actually matter, and not get too attached to all the rest.

For more: Read/watch Steve Jobs’s 2005 commencement address, try a meditation on death, talk to an elder about their experience of aging

Thing #3: Doing Good Locally

I’ve always been fascinated by historical figures like Hitler, Stalin, and Mao. These men all committed great atrocities and were responsible, directly or indirectly, for the deaths of tens of millions of people. They are, rightly, regarded as the embodiment of political evil.

And yet, each doubtless believed he was doing good for his country and for the world. Each believed that any evil acts he committed were in the name of a greater good. Hitler wanted to radically reorganize Europe politically and economically and turn it into something resembling the “co-prosperity sphere” that the Japanese wanted to establish in Asia at the time. Stalin believed that socialism would liberate the working class of the world, who would ultimately “merge into a single, global human community,” and that revolution was a necessary part of the process to get there. Mao‘s goal was to unify China and make it prosperous.

You could conclude that these men were simply delirious and power hungry, and I’m sure there’s some truth to that. It may be a bit reductionist, but another common element is the way in which they were all trying to do good on a massive, continental or planetary scale. If the twentieth century taught us one thing, it’s that large-scale politics leads to large-scale suffering. All empires were built through conquest and suffering, and all empires eventually collapse. By contrast, small entities like cities tend to survive and thrive even over very long periods of time.

What seems good locally rarely works out as planned at very large scale. This is as true of Facebook—where Mark Zuckerberg’s mission to “make the world more open and connected” has caused a great deal of harm globally—as it is of those figures from the previous century. Massively scaling things requires building a machine, and massive institutions. Trust and understanding don’t scale that way. When the machine gets too big, its creator loses control and is no longer aware of what it’s doing or why. To paraphrase Marshall McLuhan, we build our machines, then our machines shape us.

There’s so much need in the world, and so many places where we might do good. But, just as fortune is to be found close to home, so too should good be done close to home. Yes, I live in a wealthy country, and yes, there is perhaps more dire need elsewhere in absolute terms, but I think I can do the most good closest to home: in communities and among people I understand better, and whom I can meet, get to know face to face, and build trust with.

This is one reason I’ve embraced the crypto vision of decentralization. I fundamentally believe that doing good doesn’t scale. Rather than a centralized bureaucracy trying to dictate what’s best for everyone, everywhere—which never ends well—we really want a federation of locally-governed communities. More on this topic later.

For more: I’m not sure. I’ll bet there are some good books on this topic, but I haven’t found any yet. Get out there and do some good in your ‘hood!