Three Things #24: July 3, 2022

Making sense of the abortion debate, the weirdness of the Supreme Court, and where we go from here

Last week, I talked about three things I want to write about. This is not one of those topics. But it feels important enough, and the public discourse I’ve seen has been so low quality and so lopsided, that I’m going to write about it anyway.

This is a particularly challenging topic to cover for three reasons. First, it requires actively challenging my own long-held beliefs and opinions, as well as attempting to write objectively about a politically charged topic. Second, discussing the issue intelligently requires an extraordinarily large amount of context and history. I can’t possibly do that justice in the limited time and space available here, but I’ll do my best. Third, the issue is so incredibly divisive, it’s basically impossible to find straightforward, unbiased, factual information. Even the most canonical source of all, the opinions written by the Court’s own justices, are fiercely contradictory, even adversarial.

As I did with the Russia-Ukraine war and the Terra collapse, I thought it would be interesting to explore the issue from both perspectives.

Thing #1: Where Liberals are Coming From

The Supreme Court is an odd institution, full of contradictions. It has absolute power but no executive authority whatsoever to enforce that power: as Alexander Hamilton put it, it “has no influence over either the sword or the purse.” The Court derives at least some of its authority from Congress, and Congress may have power to regulate the Court. It’s the least democratic branch of government, given that none of the justices is elected. It’s obviously political but is somehow supposed to stand outside of politics. It’s supposed to interpret laws, not make them, but its opinions have increasingly begun to sound like legislation. Its behavior has historically been governed by a set of norms, but as with so much else in American politics, those norms apparently no longer apply.

What’s more, the current Court is wildly out of sync with the American population: six of the current nine justices were appointed by Republican presidents, even though Republicans have lost the popular vote in seven of the last eight presidential elections. Of the most recent 20 justices, 16 were appointed by Republicans. The Court today has a clear conservative bias. It has been skewed in the past, but norms like stare decisis (respect of precedent) and the understanding on the part of the justices that the court must act in ways that “allow people to accept its decisions” historically constrained its behavior, and allowed us to maintain the myth that it was, in some magical sense, unbiased.

Fast forward to last week when in a landmark decision, Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, the Court decided that stare decisis no longer matters, acted in the face of overwhelming public opinion to the contrary, and overturned Roe v. Wade, the 1973 ruling that had established a constitutional right to abortion. This decision is chilling for several reasons and on several levels. In choosing to offhandedly dismiss both public perception and precedent, the Court asserted that it will no longer abide by the norms and standards that constrained its behavior in the past. The Court’s conservative supermajority made clear that they recognize their power and they’re fully prepared to use it, come what may. As a result, the perceived legitimacy of the court, already in decline before this decision, will continue to erode.

This has terrifying implications for American democracy. Most of the recent presidential elections have been close, and the Supreme Court famously had to intervene in two of them. The structure of the electoral system is guaranteed to perpetuate minoritarian rule on the part of Republican senators and presidents, and there will doubtless be more close elections as a result. And it’s unclear whether Americans would accept another such decision made by such a clearly biased court, nor what would happen if they didn’t. When Democrats return to power, it’s increasingly likely that they will attempt to address the imbalance by packing the court, leading to a dangerous new form of brinksmanship, one more common in tinpot dictatorships than in the US of A.

Regardless of whether Roe v. Wade was a flawed decision, public sentiment clearly and overwhelmingly supports protection of abortion as a constitutional right. Ignoring precedent, as the Court did last week, opens the floodgates to many other historical decisions being undone, which will lead to more chaos and uncertainty.

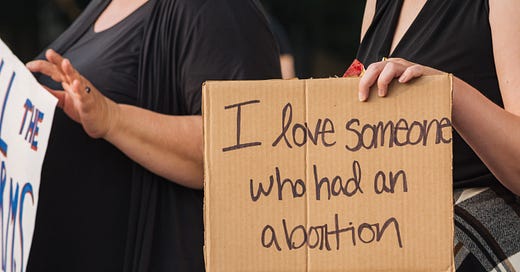

On top of these legal questions, there’s the simple, practical, humanitarian question: what will happen to millions of women for whom access to a safe abortion will become difficult or impossible? A map showing the proximity of the nearest abortion clinic around the country is legitimately terrifying. What will happen to children born to parents who don’t want them, and/or cannot afford to raise them, especially in states that offer little to no prenatal or postnatal support? As if that wasn’t bad enough, women will die as a result of this decision. Unsafe abortions cause “47,000 deaths and 5 million hospital admissions each year.” That number is bound to go up. And the decision is quixotic to boot: abortion rates are similar in countries that restrict access and countries that allow it.

The question of abortion goes directly to the question of what it means to be free. Roe v. Wade did not happen accidentally or in isolation; it was downstream of a century of landmark decisions granting ever-larger groups of Americans greater freedoms including citizenship, bodily autonomy and freedom from slavery. A person is not completely free without autonomy over not only their person but also their family: the ability to marry whomever they want, regardless of race or gender, and the ability to decide when to have children and how many children to have.

This freedom requires safe access to abortions when necessary—if not until full term, then at least up to a point, and with exceptions for cases of rape and incest. Forcing women to carry pregnancies to term is inhumane and unjust.

Thing #2: Where Conservatives are Coming From

To understand where modern conservatives are coming from, we have to zoom out a bit from Dobbs and from the Supreme Court. We have to understand some history: how liberalism arose, how it has captured American society in recent decades, what its impact has been, and how conservatives have responded. Here’s an admittedly reductionist, whirlwind tour through recent history.

Liberalism as we know it arose in the decades following World War II. It’s fundamentally about the primacy and sovereignty of the individual vs. the collective, and about individual rights and freedom. Coming out of the war years (during which everyone had to make sacrifices for the common good), and partially as a reaction against fascism and communism (which both emphasize the collective over personal liberty), Western society turned in a more liberal, individualistic direction. This was further catalyzed by the sexual revolution of the sixties. Over the following decades, more and more individual freedoms proliferated, including abortion, interracial marriage, same sex marriage, and no-fault divorce. Liberals viewed these as wins for personal freedom and sovereignty, while conservatives viewed them as a dangerous, downward spiral that put traditional social institutions like the family and church at risk.

Over time, this liberal movement gained momentum, and more and more institutions fell in thrall to it, including big corporations, especially tech and media companies. Liberalism came to dominate the hallways of American cultural power, from universities to music labels to newspapers. At the same time, through urbanization and globalization, America was also becoming more divided between an urban, liberal, globalized elite who mostly prospered from globalization, and a conservative, rural class of those left behind.

As America globalized it became wealthier and more diverse, but increasingly it lost its soul. Talented young people left their families and hometowns and joined the ranks of the urban, globalized elites. Manufacturing jobs in those same hometowns were sent overseas and rural communities around the country that had relied on them gradually hollowed out and fell into despair, first from job losses and, more recently, from the opiate epidemic. Elites continued to focus on the macroeconomic benefits of international trade, immigration, and other aspects of globalization, and paid attention to the bottom line—more trade, higher GDP—but not to the plight of the millions of Americans who were left behind, and to increasing inequality. Civil society collapsed and religious communities suffered. America got wealthier on the whole, but at what cost?

Meanwhile, conservatives responded by reforming the Republican Party: first, under Reagan, focusing on conservative bugbears like abortion, then again, more recently, under Trump’s “America First” agenda. They sought out to remake the Supreme Court, and last week they began to see success from this decades-long project. Liberals have been busy moving further and further to the left, pushing a woke agenda, and have been largely asleep at the wheel politically. Even the emergence of Donald Trump failed to force much meaningful reflection or reform of the Democratic Party, and the Party failed to capitalize on Biden’s overwhelming victory two years ago. Its political agenda is stalled, partly because of inflation caused by printing too much stimulus money.

There actually isn’t very much to say about the Dobbs decision itself. Unlike, say, the right to bear arms, the subject of another recent landmark decision, abortion was never explicitly protected in the Constitution. Roe v. Wade was a deeply flawed decision that rested on a shaky concept of a “right to privacy.” In Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which revisited Roe v. Wade in 1992, several justices pointed out these flaws, but the prior decision was upheld on the basis of stare decisis. Today’s Court made the reasonable decision that precedent alone is not sufficient reason not to overturn a flawed prior decision, no different than when Brown v. Board of Education rejected the Plessy v. Ferguson doctrine that permitted ongoing racial segregation.

Since there is no Constitutionally guaranteed right to abortion, the decision belongs in the hands of the states. This is the strength of the federal system: all powers not specifically enumerated to be in the hands of the federal government remain with the states. Those who disagree with the rules in their home state are free to move to another state. Or they can campaign for change at home, a healthy process that has already begun. They can also choose to use contraception, which is cheap, safe, and widely available (even in Mississippi)—and Constitutionally protected by a previous Supreme Court decision.

Thing #3: Where Do We Go From Here?

It should be obvious by now that there’s no simple or easy path forward. The country is extremely divided, and the division is getting worse. The Supreme Court, as a particularly egregious example of minoritarian rule, isn’t helping. Even if you believe subjectively that the Dobbs decision was correct, objectively you also have to see how the Court is rapidly losing legitimacy and how that’s dangerous for the country and for democracy.

There’s very little that liberals can do in the short term since it seems like every political route to resolution is blocked. It will be many years until Democrats have a chance to reshape the Supreme Court. It’s unlikely they’ll win both the House and the Senate in the upcoming elections, and a divided government, the filibuster, and Republican obstructionism will make it difficult for them to pass a legislative agenda. This Court is likely to continue to neuter the power of the Executive branch and the administrative state. Democratic-led states could choose not to enforce Court decisions they disagree with (just as they’ve chosen to legalize marijuana in spite of a federal ban), but this is clearly not a long term solution and would lead to greater partisanship and division.

Real reform would have to start with basics like campaign finance reform, election reform that includes fixing gerrymandering, and ensuring voter access. At least for now, however, the status quo benefits the Republicans on all of these issues and they’re unlikely to play along. Democrats therefore have no choice but to play the long game and try to expand their base and appeal to a broader array of voters, which would mean moving back towards the center and away from the more radical, leftish positions the party has embraced recently. Over the long term, this course correction should be healthy for the Party and the country.

While no one is discussing it—since, I suppose, it’s not sensational enough—we should also seriously consider depoliticizing the Supreme Court and bringing it in line with international norms. This would mean expanding the court to 16 or more seats, setting up committees so that not every justice has to weigh in on every case, and introducing term limits.

I think the only sustainable path forward is to rediscover a national narrative, something we had (defeat communism, go to the moon) but lost two or three generations ago as we got wealthier and more entitled, and as the world became more peaceful and connected. We need to agree on a common goal and vision, even while we continue to disagree on the best means to achieve it. There are plenty of possible starting points: issues where both sides agree, such as ensuring American competitiveness in an increasingly technical world vis-a-vis China through, e.g., increased education and R&D spending. There’s also reducing the cost of healthcare spending, and supporting families and kids.

But a national narrative is more than technocratic solutions to specific problems. It’s a vision of us as one people moving forward together, through adversity, overcoming differences to achieve a common aim. It helps to have a foe or a foil, and we have the perfect one today in an increasingly assertive China. A reborn America must stand for building a future that’s both prosperous and free. We have to show that, contrary to what the CCP and antidemocratic populists the world over might say, freedom and prosperity are in fact not opposing ideas. On the contrary, over the long term they’re intrinsically bound. (Of course, we also have to engage with China in a way that’s constructive and mutually respectful in order to avoid greater conflict, but that’s the topic of a future issue.)

Getting there will require a great deal more empathy than we’ve shown each other the past few years. Liberals must get off their high horses and recognize that great swaths of the country have been left behind by technology and globalization and that this is bad for all of us. If we can’t stand in solidarity with our fellow Americans, if we can’t reorient our society enough to make room for those who have been left behind, then we no longer deserve a claim to being the greatest nation on earth. There are so many ways we could start this process, from investing more in trade schools and better honoring craftswork, to radically reimagining the university experience and how it might be used to bring together students from many geographies and socio-economic groups, and teach them mutual respect and pride, rather than turning them into coddled, radicalized bundles of woke energy.

And by the same token conservatives must recognize that some degree of change, due to unstoppable trends like technology and globalization, are unstoppable. The country and the Republican Party must adapt, and not by embracing divisive populists like Donald Trump. Conservatives must understand that this degree of minoritarian rule is not sustainable, and that it’s asking for a severe liberal backlash, which might include ending the filibuster, stacking the Supreme Court, changing campaign finance laws, reforming the electoral college, or even moving towards direct democracy, all possibilities that are closer this week in the wake of Dobbs. Before this radical, liberal backlash happens—and it will, sooner or later—conservatives have to make peace with their liberal counterparts and agree to reasonable compromises that will benefit them and the entire country in the long run.

American democracy, the oldest democracy in the world, is seriously at risk today, more than I think many people realize. We still have time to turn things around, but probably not a lot of time. Abortion is a bellwether issue because it so perfectly reflects the sentiments and fears of Americans on both sides, but the fate of our democracy hinges on much bigger questions like the role of the Supreme Court and the source of its legitimacy, and the role of the federal government vis-a-vis the states. Now is a great time to have difficult conversations about these fraught topics and begin to chart a common course forward.