Lessons from Burning Man: 2024 Edition

Three Things #136: September 15, 2024

I can’t attend an event as big and important as Burning Man and not reflect on it at least a little, like I did last year. Now that I’ve had some time to decompress and process everything that happened this year, I feel prepared to write about the experience. This was my fourth burn and it didn’t disappoint. It was the longest and most intense of my Burning Man experiences. Here are some of the things I learned this year.

Thing #1: Austere ⛺

I attend Burning Man for several unrelated reasons. I do it to build physical things (as opposed to software), I do it to spend time with my amazing campmates, I do it to take a step back from the daily grind and reflect on my life, and I do it to have fun, to name just a few of my motivations.

Another big motivation is to get outside of my comfort zone. While my life is far from perfect, day to day things are pretty easy overall. I live in a big, comfortable house. I have electricity and running water and air conditioning, and a big, comfortable bed. I have a fast Internet connection and a relatively modern workstation for getting work done. I have a kitchen and plenty of food and can prepare or order more or less whatever I want whenever I want. When I want to go somewhere, I get in the car and, even with some traffic, I’m usually there pretty quickly and with a reasonable degree of comfort. The weather is usually not too bad.

At Burning Man, none of these things is true. I sleep in a tent, or a yurt, on a cot or an air mattress, with unreliable electricity at best and no power at worst. It’s freezing cold at night and boiling hot in the daytime. There’s no air conditioning, so in the hottest part of the day we do our best to hang out under shade structures out of the direct sun and we try to stay hydrated. There’s no running water, which makes it difficult to keep dishes clean, to say nothing of keeping clean ourselves without access to a shower. We get around on cheap, old, unreliable bicycles that are constantly breaking down and are one pothole away from permanent retirement. Frequent dust storms and occasional rain mean that at any time you might get stranded far away from camp with no way back. Even simple things, like brushing your teeth, taking medicine, or getting to the toilet, suddenly become inconvenient, frustrating, and challenging. The discomforts of Burning Man are legion, and they’re also a big part of the experience.

At my first and second burn, these discomforts definitely bothered me. They bothered me so much that I considered not coming back, which is a pretty normal response to this degree of frustration and discomfort when you’re used to the easy life. At my third burn, which I wrote about last year, things were significantly worse due to the unbelievable amount of rain we got. Imagine all of the depravities I just described, then add to it being huddled up, shivering, in a wet blanket and wet sheets inside a wet tent, trying to get a little bit of sleep. Imagine the toilets literally overflowing because they haven’t been serviced in days, and imagine not being able to get there, anyway, because the entire path there consists of ankle deep mud.

Something happened this year, probably connected to surviving last year’s burn. I somehow feel that I overcame the physical discomforts. I felt an amazing lightness of being this year, almost as if I was waiting the entire time for the discomfort to set in, and it never totally did. I was disproportionately, inappropriately comfortable. I didn’t mind the flakey Internet and used it as an excuse to be present and truly offline almost the entire time. I loved the cold nights and huddling up inside my (thankfully, mostly dry) blankets to stay warm. I didn’t love the hot days but I trained myself to sleep through them, even through the crazy nonstop noise, even though I’m typically an extremely light sleeper. The times I was awake during the hottest part of the day, I loved the camaraderie associated with surviving and thriving together with my campmates in spite of the conditions. I even went for a long, exhilarating bike ride one day in the intense heat and sun.

In spite of the sleeping situation, in spite of the heat, the wet, the cold, the dust, the lack of a shower, and the relatively unsatisfactory food situation, after adjusting for a day or two, I felt better than ever. I was blown away by how much energy and vigor I had. I enjoyed my day, went with my camp to see the man burn for a few hours, returned to camp, worked all night until 9am, and felt totally fine. I’ve never done that before, never, not even in the best, most comfortable circumstances!

I was amazed by this experience and how comfortable everything felt this year. I didn’t feel truly uncomfortable or out of place for a moment, and, unlike in previous years, not once did I wish to be home or that I had decided not to come. Not for a moment. Because the joy of being there so outweighed the discomfort and inconvenience.

And the feeling of coming home after more than two weeks on the road was absolutely spectacular. I felt like I was experiencing all of the joys of home for the first time: my first proper, hot shower, the first night home in my own bed, cooking a proper meal for the first time, and, of course, seeing my family again. It’s so stupidly easy to take those things for granted on a day to day basis. Burning Man is a fantastic opportunity to reset, to realize how little we really need to be happy, healthy, and comfortable, and to appreciate everything anew when we come home. Once a year is the absolute minimum that we should experience such a thing!

I want to say that I won’t take these things for granted again, but I know myself. I’ve been here before, and I know that I’ve already begun the process of normalizing these things all over again and taking them for granted in spite of my best efforts to the contrary. It will take another similar experience for me to appreciate them all anew. That’s human nature.

Thing #2: Capable 🏋♀

I’ve written about activities in the past that have shown me what I’m capable of, and how they’ve shown me that I’m capable of substantially more than I thought: things like running my first marathon, a ten day silent meditation retreat, and, yes, Burning Man. I didn’t expect to learn a lot about myself or really push myself to the limit this year, but in the event that’s more or less exactly what happened.

I first got a sense of this when my camp lead asked me to drive a monster truck (literally) to Burning Man, hauling one of the big trailers that we need to set up the art car. I drive a small sedan and I’ve never driven anything bigger than an SUV; I don’t think I’ve ever even driven a pickup truck before, let alone a monster truck. This thing is so big that at nearly two meters tall I don’t even reach the hood. And I’ve definitely never towed a trailer before.

I wouldn’t have been too worried if I were driving across town, but that’s not how Burning Man works. For one thing, we need to tow the trailers from California into Nevada, which means over the Donner Pass, an especially steep part of route 80. For another, driving to Burning Man literally means off-roading on the playa, which is full of huge ruts and isn’t exactly smooth driving. Pretty much everything about Burning Man is best effort, which among other things usually means little to no time for preparation and testing, and very limited sleep (one of the unofficial mottos of Burning Man is “safety third”). With all of these things combined I was feeling a little anxious.

Fortunately, it wasn’t my first time at Burning Man. I always have some anxiety going to the burn, and it always ultimately proves unfounded. And as already mentioned, last year was pretty rough, so I knew that that things would be a little bit easier and more relaxed this year. I decided I would take it one day at a time, take it slow, double-check absolutely everything (are those bikes on top of the trailer really ratcheted down correctly?), and, yes, sleep as much as I could.

In the event, the trucks and the trailer were totally fine. Driving in was completely anticlimactic. I had to learn a couple small things, like how to test the trailer brakes and adjust the gain, and how to use the diesel engine exhaust brakes on the truck, but the rest was easy-peasy. I like cars and I like driving and I’m even beginning to like trucks, too. I’m already thinking of getting a CDL to haul the really big trailer, or drive an even bigger truck, next year.

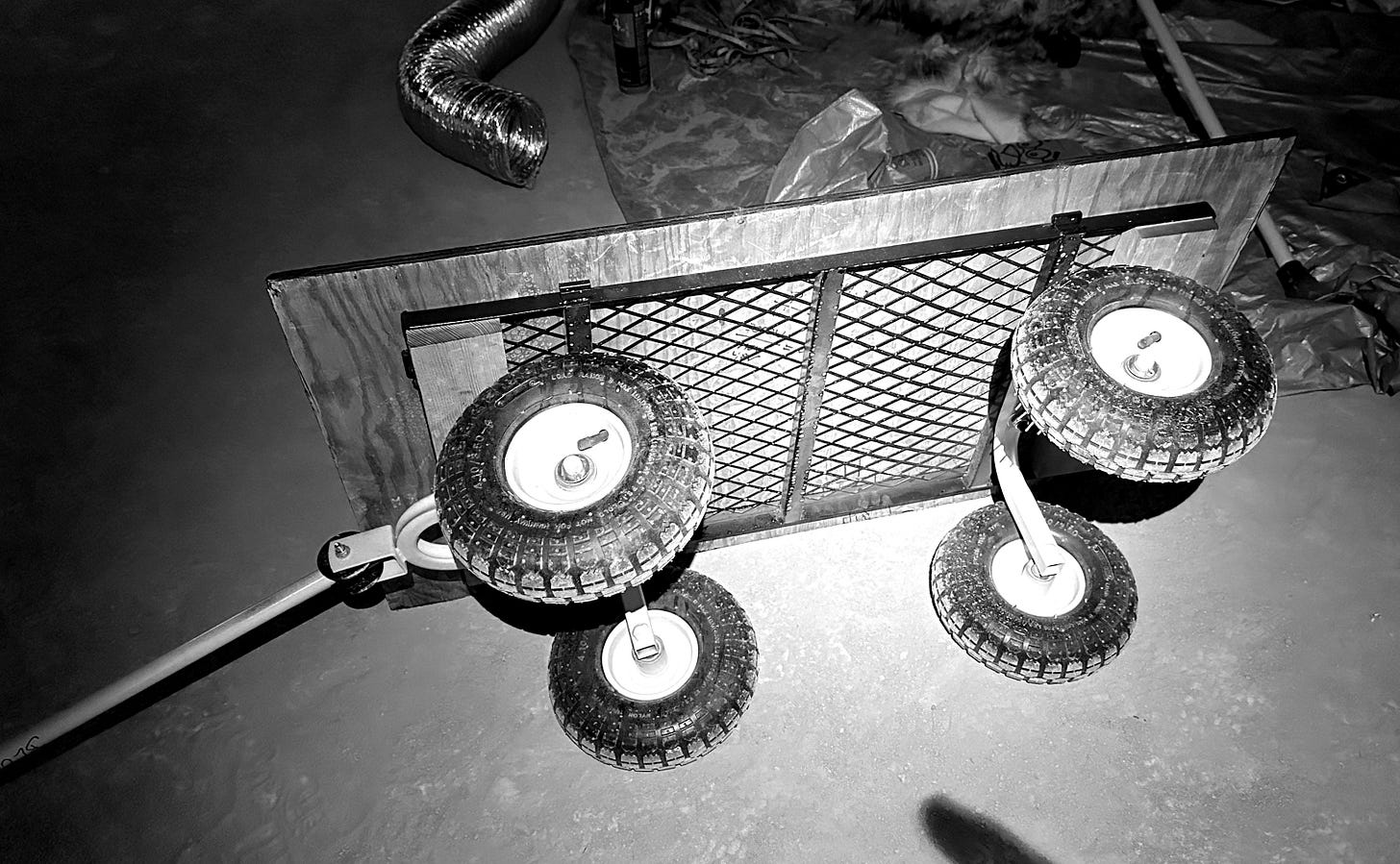

Much more intense was the work on the art car, setting it up at the beginning of the burn and striking at the end. I remember being really intimidated by this last year, too. More experienced campmates would ask me to grab them a tool or object I’d never heard of before (an “impact,” some “pex,” that sort of thing). I was handed a welding iron and told to weld two pieces of metal together, something I’d never done before and had no idea how to do (It’s easy to learn the basics, but hard to do well). I was handed a portable saw and asked to cut a bunch of wood—hopefully without losing any fingers (I didn’t lose any). And I became sore from carrying around lots of big parts: some of the wall pieces weigh hundreds of pounds, and working on the car involves a lot of manual labor in a lot of unfamiliar postures.

In the event, this was a lot of fun this year, too, and I was much more confident than last year. I’m still learning the names and uses of all of the tools and spare parts, but I’ve got most of them by now. I was tasked with designing and building something from scratch this year—I haven’t done carpentry since elementary school—and I was very proud with how it turned out (after a few false starts, of course). I stayed up all night working on the car multiple nights and was amazed that my energy level was so high, even after a long day.

While I had trouble sleeping the first few nights, mostly due to noise (it’s never actually quiet at Burning Man, especially up front where we were camped), eventually I trained myself to sleep in spite of the noise and got enough sleep to feel safe driving, even the big trucks. I didn’t injure myself, aside from a couple of small nicks and scratches (tip: wear good work gloves, basically all the time). And, amazingly, I wasn’t very sore, even after all the lifting, carrying, and holding, proof that my time in the gym the past year is paying off—the best possible sort of validation.

In line with realizing how little I need to be comfortable—Burning Man this year was an excellent lesson in what I’m capable of. It turns out that I’m capable of a lot of things I didn’t know or imagine, and it just takes exposure, opportunity, encouragement, and a little bit of courage to figure this out. This is another reason I love Burning Man so much: it shows me what I’m made of, and it introduces me to all sorts of new skills and ideas, some of which stick even back in the default world. I’m not going to stop coding anytime soon, but I also love the feeling of building something tangible—and more to the point, of feeling capable of building tangible things.

Thing #3: Free 🍑

One of the first things that strikes first time burners is the prevalence of nudity at Burning Man. There are naked races. There are naked kitchens and naked gyms. There are plenty of “side show” camps that you inevitably, unavoidably pass while going about your business around town, that involve things from exhibitionist dungeon play and spanking, to strip games, to shibari. And there’s a lot of people who just go about their daily business, from brushing their teeth, to cooking lunch, to going for a walk, in the nude.

Some forms of nudity make sense to me. For instance, one of the most famous camps at Burning Man every year is the foam camp sponsored by the Dr. Bronner’s company. This involves stripping down, getting doused head to toe in foam inside a transparent trailer surrounded by strangers, subsequently getting rinsed off, and finally, a naked dance party while everyone air dries. To be clear, most burners haven’t had a shower in a few days, so this particular camp makes a lot of sense (it’s also fun, take my word for it).

The rest of it doesn’t make a lot of sense to me. I never saw the appeal of being naked in public, especially when it doesn’t involve something pragmatic like, you know, taking a foam bath in the desert. To me, it makes even less sense given the hot weather and strong sun: the last thing you want to do in the desert during the daytime is to expose all of your skin and sensitive bits to the sun, and at night it’s way too cold. But one of the Burning Man principles is radical self expression, which usually manifests in strange situations as one person looking questioningly at the odd behavior of another, shrugging, and saying, “You do you, man.” While I don’t see the appeal of gratuitous public nudity, I also see no harm in it and it doesn’t bother me at all. Upon arrival it’s strange for about the first five minutes. Then it becomes normalized and you basically stop noticing it.

This year, though, something else began sneaking up on me: a feeling of celebration. I think I crossed a line this year with respect to my feelings towards all of this nakedness, too. You see, my camp runs a steam room art car that involves, you guessed it, an exceptionally high degree of gratuitous public nakedness. People shower in public, then enter a steam room with a bunch of strangers, and then most people end up dancing naked on top of the car while they air dry, putting on a show for everyone on the ground. Sometimes they stay there for hours. There’s something magic and liberating about dancing nude in the middle of the desert on top of an art car (take my word for this, too). I’m beginning to understand why this appeals to so many people. Burning Man is all about throwing off everyday, “default world” social convention, and public nakedness has something to do with flagrantly ditching one of the last vestiges (pun intended) of default world society during those magical days at the burn.

Here’s how the night unfolds. We pick a spot on the playa and arrive shortly after sunset. There’s a common pattern: first timers find the car, lured either by rumors they heard or else by the flashing, multicolored lights and great DJs that play the car. They hesitate. They stare in disbelief at what their eyes are telling them. They turn to their friends, or their partner, in conference, and discuss whether they’re up for it. Occasionally they walk away, shaking their heads, muttering something like, “I’m pretty warm right now, thank you very much.”

But more often than not they jump in. Strength in numbers helps: there’s always people waiting in line, sometimes a dozen or more, and they’re all standing around awkwardly, not wearing anything, so joining them is an act of solidarity. A very few choose to wear a bathing suit, but 99% go whole hog. You make friends with people in the nude, and something about the vulnerability of being exposed together in public, and the sheer absurdity of the situation, allows you to go deep, fast. (The Japanese have a really wonderful word for this.) You cross paths again later and don’t recognize them with their clothes on, which makes you giggle.

The stories and the smiles tell the tale. They come out the other end transformed. They say they’ve never experienced a steam room before, never been naked in public before. Some tell stories about how they spend every day in the default world ashamed of their bodies, and that their experience on the art car at Burning Man is the first time in their lives they’ve ever been able to celebrate their bodies. Without a doubt, the experience brings a lot of joy to a lot of people, and I don’t think it’s an exaggeration to say that it’s really transformational for many.

It’s a lot of work to bring this experience to the few hundred people who get to experience it every burn: months of planning, weeks of labor maintaining the car, setting it up, operating it, taking it back down, etc., to say nothing of the cost. But the smiles, stories, joy, and connections it generates more than make up for it. This is what Burning Man is all about. One of the core Burning Man principles is gifting, and service is one of my most important core values. Is it strange to say that this is one of the most powerful forms of service in my life today?

And upon returning home, a strange sort of flippening happens. I begin wondering, why do we spend so much time and money on these awful clothes that we’re forced to wear most of the time? What makes this behavior any more normal or rational than wearing your birthday suit? It’s not so obvious anymore. As with so much about Burning Man, you’re left questioning things you never even noticed or considered before, and missing the magic of the playa. And that, too, is the point of Burning Man: revisiting even the most basic social conventions from first principles.