“Spacemesh is different” has become a common theme here. I’ve written about the topic again and again from several different angles, to the point where it almost sounds cliche. Perhaps we should think about making this our official network slogan. (Oops, I guess someone already did that.)

When I talk about Spacemesh being different I’m usually talking about the technology. I’ve also written a little bit about some of the contrarian non-technical decisions we’ve made, but I want to explore a particular aspect this week: the social aspect, and in particular, how we think about leadership at Spacemesh.

Thing #1: Charisma 🧲

“If you want to build a ship, don't drum up people to collect wood and don't assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.” - Antoine de Saint Exupéry

The canonical, received wisdom about leadership is that successful companies and projects need strong, charismatic, visible leaders. This is certainly what I was taught in both business school and in “startup school.” In my experience it’s also true in practice. The stereotypical image of a successful leader is that of a general leading the army into battle, riding proudly at the front of the pack flying the banner, a la Napoleon or Braveheart.

Teams need strong, visible, charismatic leaders for a host of reasons. The most obvious reason is motivation and inspiration. The leader sets the stage and the tone for a project and team. The leader sets the example and is the most obvious person to model successful, appropriate behavior and culture for the team. Some of the behaviors that the leader needs to model are fairly obvious: showing up on time, being held accountable for your actions, doing what you say you will, generally working hard, acting responsibly and with integrity, etc.. Some behaviors that are less obvious are even more important, namely acting in a moral and ethical fashion. If the leader doesn’t model this behavior or isn’t capable of modeling it, no one will.

The leader is the person responsible for recruiting people to the team and for ensuring morale stays high especially when times are tough. I personally think these are the two most important qualities and responsibilities of a leader: recruiting talent and retaining talent by keeping people motivated and happy. (Sales is probably the next most important.)

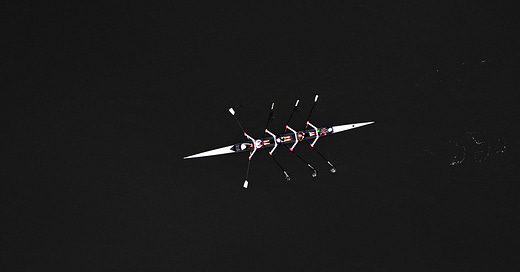

The leader is also essential for decision making and consensus formation. If they’ve done their job and recruited a diverse team of talented people those team members will have competing opinions and will naturally pull in many directions. The leader has to bang the drum, so to speak, to make sure that everyone is pulling at the same time and rowing in the same direction; otherwise the project will just go in circles. I’ve seen what happens when this is missing: I’ve been part of a number of teams with incredibly talented team members, which nevertheless didn’t go anywhere for lack of strong leadership and coordination.

Just as blockchains have many different consensus mechanisms there are also many different governance structures and decision-making apparatuses that teams can rely on, from holacracy and democracy to dictatorship. But no one can deny that having a single, strong, trusted, responsible leader, i.e., a benevolent dictator is the most efficient. Efficiency isn’t everything but efficiency in decision making is critical to success in a startup.

Finally and most importantly the leader needs to have the vision. This is closely related to the above points about the leader setting an example and directing decision making but also subtly different. A leader can appear to work very hard and be very decisive in making executive decisions but still not have a clear vision for what a team is building, for whom, and why.

In my experience teams that aren’t led by a leader with a strong, clear vision that they’re able to articulate and sell, both to their team and to the world, will seriously struggle. One reason is motivation. Working hard and making decisions works until it doesn’t: when things go wrong the vision is the thing that gets a team through. It’s the thing that allows the team to be agile and change direction but keep working towards what matters most.

Another reason is focus. There are always a thousand things to do and startups are always pulled in a thousand different directions: by customers, contractors, team members, journalists, lawyers, advisors, investors, etc. Having a clear vision makes deciding what to do very simple. The leader can always ask, Does this clearly further our mission and get us closer to our vision? If not, the answer should be no.

To reiterate: the vision is what keeps a leader and their team going when times get tough, as they inevitably will. Building a startup and a product is the hardest thing you’ll ever do; I liken it to pushing an elephant up a very long, steep staircase. Visualization is an extraordinarily powerful tool, as powerful in business as it is in sports, and a strong leader’s clear vision is quite literally the one thing that can and will get a team through those dark moments when it feels like the sky is falling (which, honestly, is most of the time at most startups).

A strong leader with a clear vision will be able to sell it to potential team members, investors, and customers; it’s their secret weapon and their magical fairy dust. A leader without such a clear vision has to work ten times as hard and will struggle with all of these tasks. And a vision is most effective when articulated by one person; it’s nearly impossible to recruit others to share your precise vision. So the leader, the one with the authority to make it actually happen, has to be the one with the vision.

Finally, a leader should be likable. There are different successful founder and leader archetypes. Steve Jobs was notorious for being difficult to work with and not very agreeable but he’s the exception that proves the rule. In my experience a likable, charismatic founder with a confident persona goes a very long way towards getting employees, investors, and customers onboard. And a company without such a leader, or with an unlikeable leader, is at an enormous disadvantage.

Thing #2: Corruption 😈

“Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Great men are almost always bad men… There is no worse heresy than that the office sanctifies the holder of it.” - John Emerich Edward Dalberg, Lord Acton

Decentralization is the name of the game. It’s why we started and it’s the reason we’re all here. Yes, decentralization is about building resilient technical infrastructure but it’s equally about building resilient social infrastructure. In the same way that a system run by a single, centralized server isn’t resilient against faults or attack an organization run by a single, strong, charismatic leader is equally susceptible to these same problems.

It’s a tale as old as time: the king can make decisions efficiently, but the king is only human and is subject to human weaknesses including corruption, vanity, and pride. The king ages and over time his ability to make good decisions diminishes. The king’s understanding of the nuance of a situation and his ability to see things from others’ perspectives are both limited. If he’s wise he’ll surround himself with advisors that will address some of these shortcomings, but those advisors may also try to take advantage of him and his power and authority.

Absolute power corrupts absolutely; in my experience there are no exceptions to this iron law. It doesn’t matter how well intentioned or how benevolent the leader is in the beginning. If the organization succeeds and the leader’s decisions begin to really matter the corruption process has already begun. Inevitably once this process starts, vanity kicks in and it becomes more about the leader than about the project. The leader starts making decisions in the interest of the leader and not necessarily of the organization, team, or community, or the longevity of the project.

If we wanted kings and strong, charismatic dictators for life, we wouldn’t invest as much time as we are in building novel social and technical architecture. We wouldn’t be focused on decentralized, permissionless, censorship resistant, credibly neutral consensus infrastructure. We could just run regular, centralized companies with centralized leadership, boards, and ownership, and we could just run regular, centralized databases. This is the way things have always been done and it’s much easier. But we can and must do better.

Leadership will never be immune from corruption as long as there’s a single, central, privileged actor. In the same way that the administrator of a database backing a valuable system will invariably be corrupted into taking advantage of the ordinary users of the system, whether by printing more money for themselves and their cronies, by selling user data and otherwise exploiting users, or by enabling “god mode,” an organization with a single leader will never be safe from corruption.

This is why it’s so important to decentralize power, control, and decision making authority away from one person. The wisest founders and executives understand this dilemma. They understand their own human failings, sometimes even before their team or the world does, and they take steps to reduce key man risk, cult of personality, and other ways in which the organization overly relies on them.

The only sensible answer is good governance, which means decentralizing power out of one person’s hands. Rather than one leader, an organization should have several. There’s no universally perfect number, but five is usually close to ideal: it’s enough people to ensure that many perspectives are heard and to ensure a reasonable degree of diversity in discussions and decision making, but it’s few enough that it’s still not too hard to achieve consensus and make decisions.

Checks and balances are important. Many of the same things that can happen to a single leader, such as corruption, can happen to a group of people, too. The “executive committee” needs to be accountable to someone, ideally to a board. The board should be larger and even more diverse than the committee. The board should be incentive-aligned to do what’s best for the company. And the board itself should answer to the shareholders. There should ideally be many shareholders that represent very diverse perspectives. This ultimate rooting of authority into many hands is the only system we’ve devised that does a reasonably good job of mitigating corruption and other failures on the part of the leaders, if only by making them replaceable when this inevitably happens.

It’s essential that a project or organization not become a cult of personality and not define itself too much in terms of one person or one personality. Because that person won’t be around forever, and because that person is a corruptible human being. No matter how strong a leader or how much of a visionary that person is, it’s important that the thing that matter be the project and the organization itself and the community behind it. To the extent that the leader matters it must be because the office matters rather than the person occupying it. This is the best way to ensure successful leadership over the long run.

Thing #3: Compromise 🤝

“We reject: kings, presidents, and voting. We believe in: rough consensus and running code.” - David Clark

We need strong, charismatic leaders that have vision. We reject centralized leadership and we recognize that all leaders are corruptible. On the face of it these two ideas seem irreconcilable, but this isn’t quite the case. I see three ways to make this work.

The first is term limits. For all of the flaws of the US government, the founding fathers got one thing right. The office of president makes a lot of sense. The president is by definition a strong, charismatic leader but his powers and his term are limited. This is a good starting point. There’s nothing wrong with strong leadership as long as leaders don’t have unlimited power and as long as there’s a periodic rotation of leaders. As mentioned above, the important thing is that the power reside with the office and not with the person currently occupying the office. Frequent rotation of leaders is the only technology we have to ensure this.

The second is checks and balances. The president can’t make and execute decisions on his own. He has to convince his party to support him, pass appropriate legislation, and appropriate funding for any initiative. (Incidentally this is why executive orders are bad and work against the idea of checks and balances.) The president is accountable to Congress, to the Court, and ultimately to the People. If he does a poor job he won’t be reelected, and if he does something really egregious he’ll be impeached and convicted. (I recognize that in practice the system may not be working as intended but I don’t think it’s an inherent flaw in the design.) This accountability and these checks and balances keep strong, charismatic leadership in check.

The third is competition among leaders or multipolar governance. Strong, charismatic leadership is less worrisome when there are many such leaders. This is admittedly harder to achieve and it’s rare in practice but it’s a wonderful thing when it happens. The US government doesn’t really work this way (the president is disproportionately dominant) but in other governments there’s more of a balance of power among a president, a prime minister, and sometimes a speaker or another powerful figure. Having multiple strong leaders, each with a vision, can be healthy when those leaders work together and when there’s significant overlap in their vision. Of course it can also descend into chaos and conflict when this isn’t the case or when there’s too strong of an incentive to consolidate power.

Of all the projects, companies, and teams I’ve been a part of over the years I’ve only seen this done well once, when the founder of a company I formerly worked for stepped down as CEO and appointed five people to an executive committee that took over the day to day management of the company. The founder took a back seat, provided oversight, acted as chair, and gave powerful speeches from time to time in order to motivate the team and boost morale, but the day to day decision making authority was divided among the anointed five. This sort of structure is especially effective when the leaders who share power do so as part of some formal governance structure where they’re deadlocked if they can’t agree on at least some things, as in this case.

Spacemesh has achieved a reasonable degree of compromise. We don’t have a formal executive committee but we also don’t have a single, dominant leader. People are often surprised to learn that I’m not the leader. Nor am I the CEO, nor the founder. I’m just an opinionated, vocal, gregarious team member. I’m one leader among many.

Spacemesh is unique among nearly all successful blockchain projects in this lack of centralized leadership. It’s an experiment and it probably wouldn’t work for most teams but it seems to be working so far for us. We have a number of respected, accomplished team members who independently have a strong vision for Spacemesh. No one person makes decisions. We do so in consensus or not at all, by design. Sometimes that consensus takes a while to achieve (as in the case of the VM), but I can say with confidence after doing this for five years that in the end we arrive at better decisions than we would if one person were making decisions about everything.

That said we can definitely do better. We need to work harder to have a shared Spacemesh vision and roadmap, rather than each person having a different version in their head. And we need to work harder to inspire other leaders to step forward. It’s still a little early to think about governance but having many leaders with competing (and overlapping) visions for Spacemesh that are ultimately accountable to node operators and community members seems like a pretty good place to start.

I’m not totally convinced that we can succeed without a single, charismatic leader with a compelling vision. That’s the way most startups succeed (or fail) and as I said I’ve only ever seen divided leadership succeed once in my own career. But I think it’s worth trying because the potential upside in terms of project health and longevity is enormous. This is another of the many ways that Spacemesh is boldly defying the odds and blazing its own trail, and I’m proud of that.